Orange

January 6, 2022

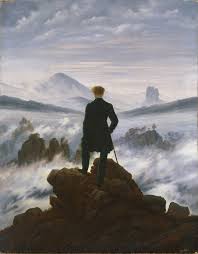

If she was a color, she would be blue. With as many interpretations of the color as stars in the sky, she had to admit, she wasn’t ashamed of her aura. With days sometimes drawing out as long as the musky grayish brown, splatters of a murky blue would paint the drab canvas. She often thought of herself as nothing more than a smear of bland steel blue, barely noticeable against the equally boring gray.

A depressing thought, she had to admit. Most days were cloudy in Seattle, and the same could be said for her mind. With a color as broad as blue, she would think her life would be more expressive. She longed for a simple glimpse of cyan to be streaked across her mind, distracting her from the brown streets, the brown houses, the brown sky.

But the streak never came. For years, she dragged herself through the motions. She woke up as a sickly glaucous, heading to school faded denim. By the end of the day, she wouldn’t even consider herself a blue—she had become so tainted by the brown muck her color was indistinguishable from the rest. Of course, it was normal.

Everyone was brownish-gray, hiding under a layer of grime to conceal their color. She never dared ask what her mother’s color was, and her brother learned quickly that manners in their household meant never asking another person what their color was. One time as a toddler, she had waddled up to a stranger in the supermarket.

“Miss?” She had tugged on the lady’s brown corduroys, looking up at the boring woman with wide, curious eyes. “What color are you?”

The lady had looked so horrified from the question, as though astonished such a young child could understand the world was filled with hidden colors. One glance her mother had taken at the action had made it so the girl knew nothing else about the colors. Once, when she was eleven, she spoke up again. “If there are more people than colors, won’t I find someone the same color as me?”

The question was met with a heavy silence like the table hadn’t thought of such a thing before. The girl just picked up her gray plastic fork, pushing her white rice to the side of her plate. “There is no such thing as colors,” her mother snapped forcefully. “Eat your peas. They’re not for decoration,”

The girl learned to never bring up colors around her family. Though, every Sunday when the clock hit four twenty-seven, the girl would slip through the silent house to the singular bathroom. Once inside, she would turn the lock and push open the bottom left cabinet of the vanity. A singular bar of soap lay inside a ceramic box decorated with small flowers; she loved that box.

Carefully, she would extract the cream-colored bar of soap, running the tap of the sink and keeping her eyes trained on the light under the sliver of the bathroom door. She waited with bated breath, her eyes scanning the area for shadows that looked like feet before turning back to the mirror in front of her.

And then she would scrub. For minutes, she would rub at her grayish skin until it turned pink from irritation. She would stare at herself, her murky eyes swimming with indigo if she stared hard enough. After minutes of relentless scrubbing, the dirt had slipped off her skin and onto the marble below, clumping up as though in need of warmth now that it had lost its owner. But she didn’t feel sorry for losing the dead gray as she stared at her arm. No matter how many times she saw the bright hues in all their glory, it managed to leave her speechless.

It was beautiful. She once swore that she saw a flash of gold slide down the vein from her left shoulder to her middle finger one night, though after never seeing it again, she had given up on the flecks of gold.

After admiring the shimmering patterns that seemed to play the girl’s skin like a piano, she would place the bar back in the ceramic box before carefully sliding her belongings back into her drawer and away from prying eyes. She would then tiptoe back to her room across the hall, her eyes shut tightly as though that would make her invisible. Once she reunited with her drabbed, she would rest her head on the dirty pillow and stare at her bright blue skin.

It had always intrigued her to guess what everyone’s color was. She knew the librarian’s color had to be warm—she was thinking a burnt orange or a soft yellow. Her mother’s, though, was definitely as dreary as everything around her; it seemed like everything her mother touched turned to gray and withered in front of her eyes.

But maybe, just maybe, she was unique. What if everyone’s color was a brownish-gray, and her bright blue anomaly was a mistake. Maybe her color should be shameful, and she shouldn’t wash away the layers of grime to uncover the vibrant shade beneath. The longer she would think about it, the more her head would hurt. So she slowly became introverted—she slowly began to hide her color just as the world around her did.

And when she was in the supermarket one day, wandering the aisles to find the bland crackers her mother asked her to find, a little boy rushed up to her, eyes bright and innocent. “Miss, miss!” He gushed, stopping a few inches short of her faded khakis. “What color are you?”

She had frozen just like the lady she had asked the same question to. The words were unspoken in Seattle. Colors are real, but not to the public.

“I’m not sure what you’re talking about,” the girl lied, turning her back on the boy and walking fast towards the checkout counter. But she knew what he was talking about; she knew now that everyone had a hidden color.

“I’m orange! The coolest color!” He yelled after her, not dejected in the slightest that she had walked away from her. The girl just smiled as she checked out her mother’s belongings, elated at the news. She wasn’t alone anymore.