The Rise of Digitalized Art

March 21, 2022

Recently I visited the immersive Frida Kahlo exhibit in Boston, which was produced by the same director of the immersive Van Gogh exhibit. Digitized art has been on the rise for a while now, but these exhibits mark a turning point in how art is being portrayed to viewers, and how that art is experienced by the viewers.

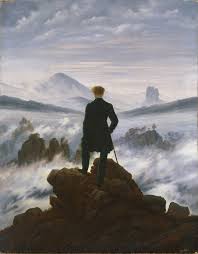

As you walk into the exhibition room Kahlo’s artwork greets you as moving projections accompanied by dim lighting. The show lasts 40 minutes and tells the story of Kahlo’s life using some of her most famous works. Similar to the immersive Van Gogh exhibit, there is a soundtrack that plays in the background as viewers either sit and watch the projections or walk around to different areas of the exhibit. Many people have praised these immersive exhibits for their innovative structure, while others are left questioning the implications of changing the mediums of art so drastically from their original. Van Gogh’s original “The Starry Night” measures 30 x 36 inches, while the immersive exhibit projects the work on walls measuring 300,000 cubic feet; quite a considerable change. Can digitizing art that has only ever been viewed in its primary state change the way people interact with it? Can it change the way people interpret the artist’s message? And if it does, are these negative or positive changes?

Art Professor C. Shaw-Smith juggles the implications of immersive art exhibits in an interview with writer Jay Pfeifer. In his classes, Shaw-Smith focuses on the intention of the hand, why artists paint in the manner they do. He states, “I can’t tell you how many students I’ve had who would say, “I didn’t realize you could see the brushstrokes” after seeing one of Van Gogh’s paintings in person. And that’s really what’s essential.” However, the digitized “immersive” exhibits, such as Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo, take away this understanding. The projection not only distorts the true nature of the art but can sometimes blur the brushstrokes themselves, not allowing the viewer to access a complete understanding of the work.

These immersive exhibits are certainly a milestone in fighting to make art more accessible. Not everybody can go to see “Starry Night” whenever they’d like, and these exhibits are arguably more representative of the real-life paintings than a google image would be. Yet even in the digital age of creation, something seems amiss with these exhibits, something that simply cannot be digitized. In Shaw-Smiths opinion, these immersive exhibits can and most likely do change the way people interpret art, but not necessarily in a bad way. The immersive exhibit is for the eye as Shaw-Smith says, not the hand. He states, “The sense of the human being who created the painting is diminished.” But even worse is never being able to experience this art in one’s lifetime, only ever seeing it through google image searches or on t-shirts being sold at a kiosk. Overall it is essential to remember the context in which art is viewed, and embrace the way it shapes our perspectives.